Adults should understand how muscle health contributes to overall health and wellness and how age-related muscle loss can threaten the body’s condition and overall quality of life. Mature adults who practice positive muscle supporting habits, like healthy nutrition and exercise, enable themselves with improved mobility and energy. Both factors can empower aging adults to live self-sufficient and more satisfying lives.

Advances in nutrition and medicine have gifted humanity with a longer average life expectancy. Unfortunately, with prolonged life comes prolonged risk of age-related ailments.

Although some age-associated disorders, such as cognitive decline and loss of bone mass, have drawn extensive media attention, moderate loss of muscle tone occurs in approximately 70.7% of males and 41.9% of females aged 65 or older, according to the journal Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience.

Declining strength and health benefits related to loss of skeletal muscle mass, if left unchecked, can lead to physical debilitation, poor quality of life, fall risk, and even death. Its widespread occurrence and long-term nature make it one of the greatest threats to elderly health and independence in aging adults.

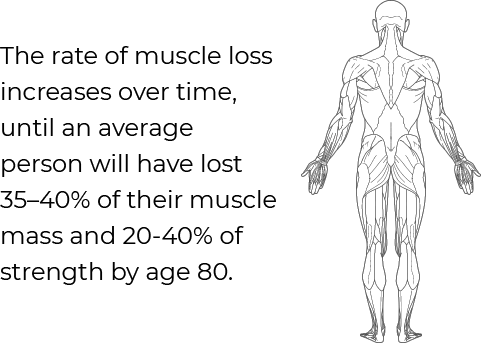

According to WebMD, “physically inactive people can lose as much as 3 to 5% of their muscle mass each decade after age 30.” Furthermore, “muscle loss accelerates after age 40 and continues to accelerate until 35–40% of total muscle mass and 20-40% of strength is lost by age 80,” according to research from Muscle, Ligaments, and Tendons Journal.

Musculoskeletal deterioration yields severe consequences for aging adults. Losing muscle can impair mobility and balance, increasing the risk of falls and fractures.

Many factors influence the trajectory and acceleration of muscle loss with age. Chronic physical inactivity and sedentary behavior, for example, may accelerate the process.

Seniors that experience even a relatively short time of inactivity, such as ten days of bed rest, may suffer a 12% loss of lower leg strength and aerobic capacity, according to research published in the journal, Medical Science. An average 7% reduction in physical activity, after the bed rest program, further aggravates the physical deterioration caused by the inactivity.

Poor diet and loss of appetite also accelerate muscle decline. Both lead to insufficient nutrient intake and, hence, insufficient bodily resources required to maintain healthy muscles.